Book Four

END

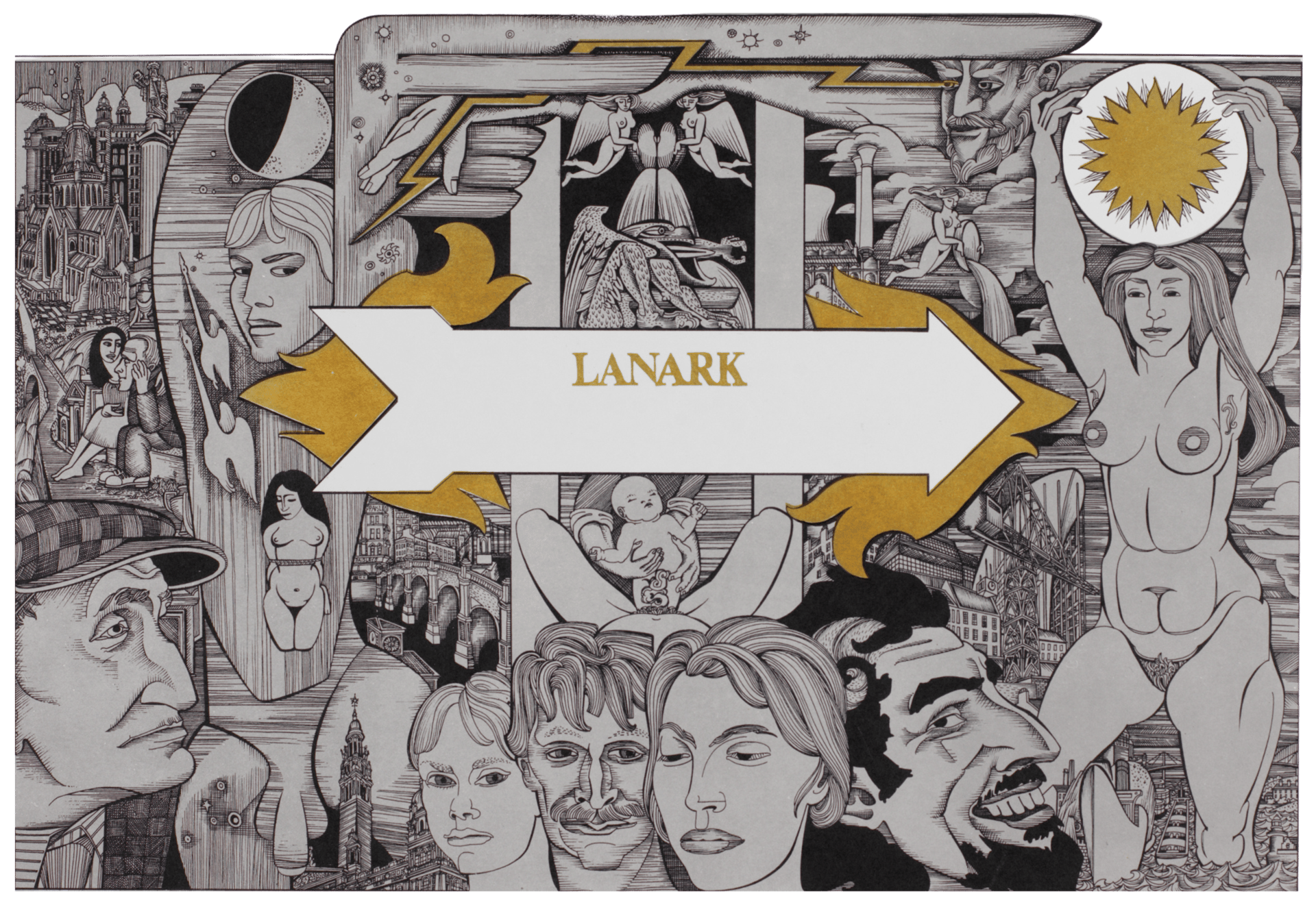

n 1975, having roamed through Glasgow’s public libraries only to find himself wandering up a staircase to an elite café via detours through institutions both real and imagined, Lanark’s author arrived at the Old London Reading Room of the British Museum. Directly prior to entering what he described as the 'great circular chamber where Marx, Bernard Shaw and Lenin had educated themselves', Gray found himself in a souvenir gift shop. Is there is no escape from the trappings of capitalism, our socialist father figures would no doubt have whispered. There among replica coins, decorative mugs and themed umbrellas (no doubt), Gray saw four 'richly symbolic' images reproduced in postcard form.

Frontispieces for Walter Raleigh History of the World (1614); Francis Bacon Novum Organum (1620); Vesalius De Humani Corporis Fabrica (1543); Hobbes Leviathan (1651), The British Museum

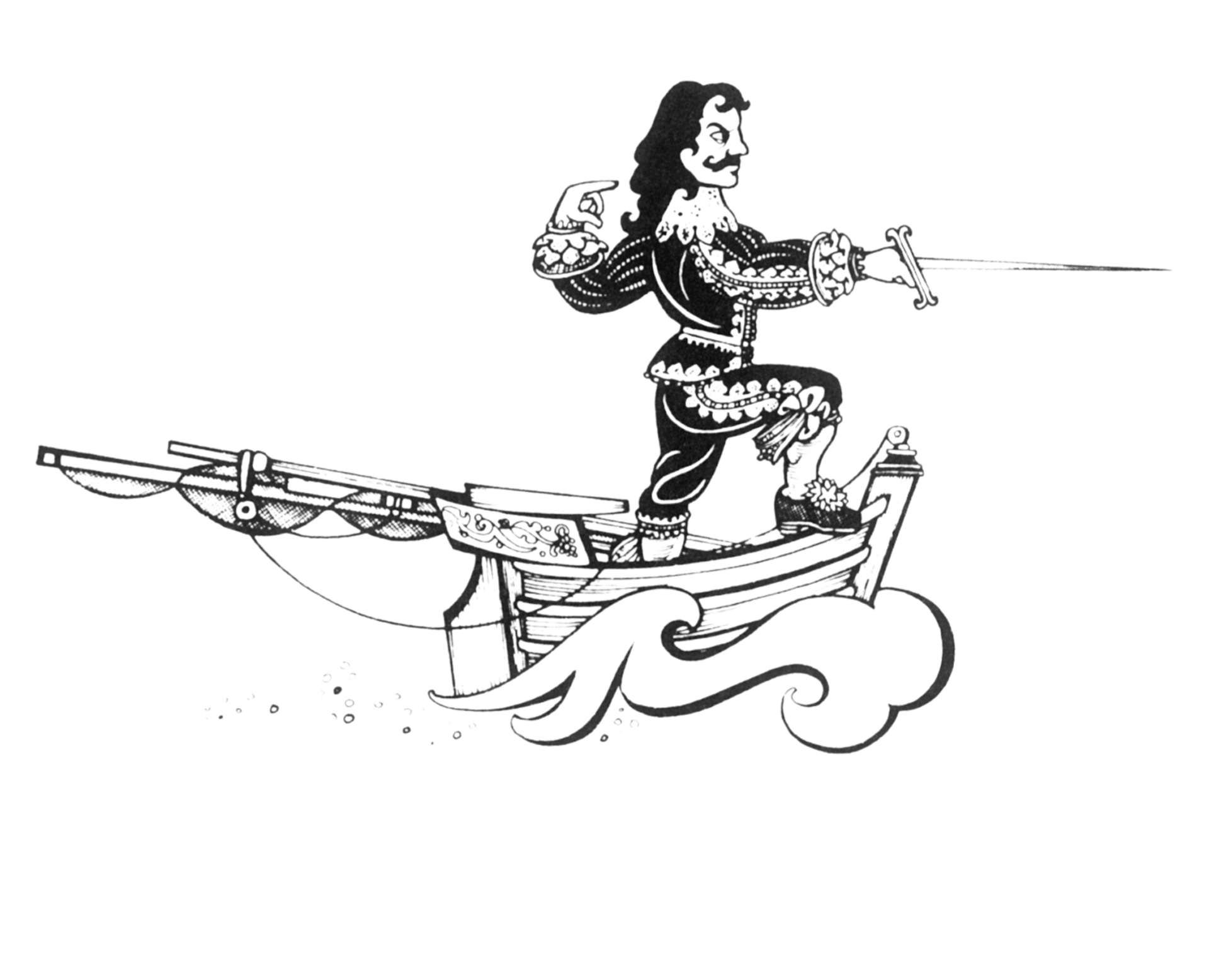

The four postcards can likely be seen on fridges across the globe, with 'Dear Mum, London great. Soaking up culture, shame about the rain' scrawled on the back. The images can also be seen on the title pages of four major Renaissance texts: Walter Raleigh's History of the World (1614), Francis Bacon's Novum Organum (1620), Vesalius De Humani Corporis Fabrica (1543), and Hobbes Leviathan (1651).

Back in 1975, as the glossy postcard replicas glistened before his eyes, Gray mused: these were books that 'advanced the arts of medicine, history, experimental science and politics'. These were books whose images 'could be adapted to introduce the four quarters of my encyclopedic novel, Lanark’, he later noted.

And adapt them he did. To see how each design compares, simply slide between each of the images below.

Lanark, Book Three, title page (2014), courtesy The Alasdair Gray Archive (AGA); Walter Raleigh, History of the World (1614), The British Museum.

Lanark, Book One, title page (2014), courtesy AGA; Francis Bacon, Novum Organum (1620) The British Museum

Lanark, Book Two, title page (2014), courtesy AGA; Vesalius De Humani Corporis Fabrica (1543) , The British Museum

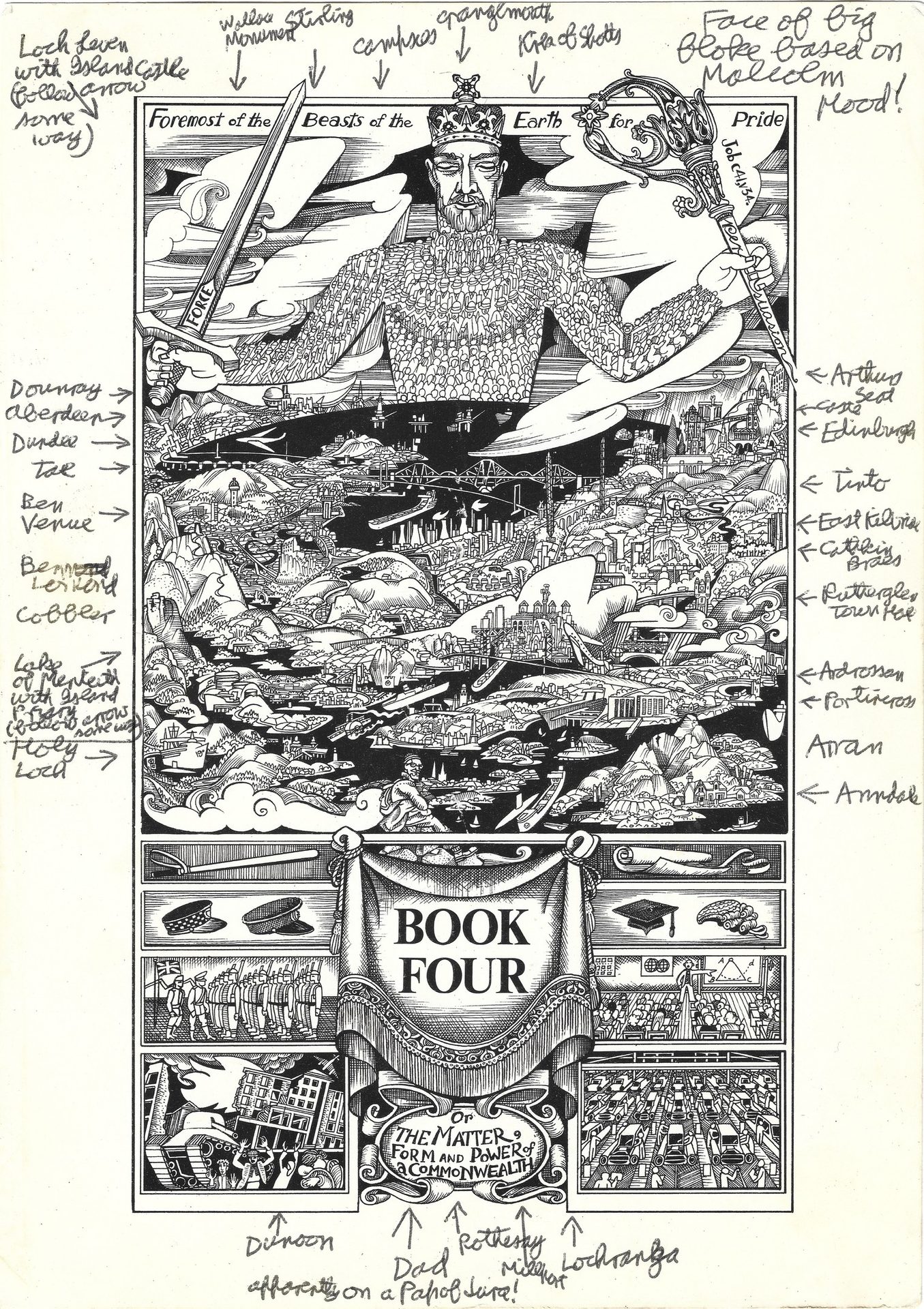

Lanark, Book Four, title page (2014), courtesy AGA; Hobbes Leviathan (1651), The British Museum

Although the similarity between each pairing is evident, their correspondence is not purely imagistic. By drawing a line between Lanark and the four tomes that ‘advanced [their distinct] arts’, as you might recall Gray noting, the writer discloses his ambitions for his own great opus. The critical reception to Lanark proved these ambitions to be less fantastical than its content. ‘Lanark changed everything’, said the late Edwin Morgan. ‘It changed everything for Alasdair personally, but also helped to change the landscape for Scottish writers’.

Horizons suddenly broadened as London-based publishers looked toward Scotland with a renewed perspective. Increased interest in Scottish literary output, catalysed by Lanark’s critical success, saw greater publication opportunities for Scottish writers. It marked the dawning of a second Scottish Literary Renaissance of which 'Gray was the heart', notes author Ali Smith. Although crowned the founding father of a new movement, Gray holds little vestige of Hobbes’ Sovereign King. The costly publication of his hand-illustrated books resulted in a less than kingly income for the artist-writer. His habit of distributing much of his earnings to social causes (Thatcher’s miners included) equally demonstrates a generosity lacking in many a leader (see brackets above). Gray’s absent grandeur equally stems from his practice of populating his works with people and places close to hand. It is not Vesalius' Galen, Raleigh's Venus, or Bacon's straights of Gibraltar that grace the title page of Gray’s Book Four. It is the faces of people he knew and respected. It's the cities and towns in Scotland through which he walked and admired.

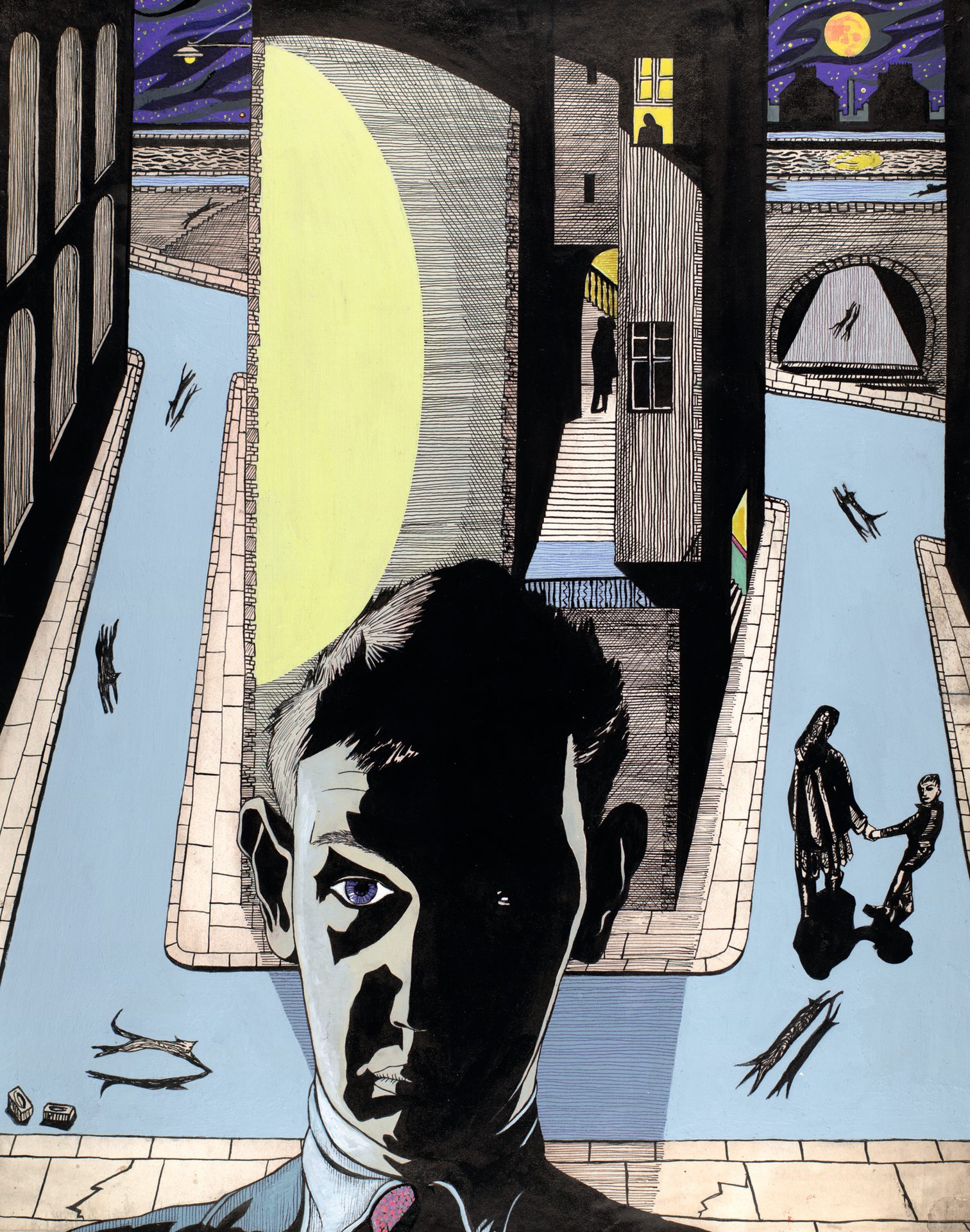

Look to the image below. You'll see a copy of the black and white ink drawing used to illustrate Book Four (Lanark, 1981). You'll see that the image is also accompanied by annotations in Gray's hand.

Lanark, Book Four (1981), annotated title page, courtesy of Mora Rolley

The horizons of Book Four's title page are multiple. The image gathers views from several cities and towns and merges them under what we can consider the 'physical horizon': the horizontal line which cuts vertically across the page. Like the Òran Mór mural, each of these views also contains a diffuse number of meanings and associations, differing from viewer to viewer and again from viewer to artist. At the same time, the work in question also elicits a subnarrative about Gray's creative practice. All of the above might be considered part of the work's 'non-physical horizon': the multi-directional stories that sit beneath the surface of any art object whether it's written, drawn, painted, or sculpted, and so on. By focussing on three key aspects of Gray's practice that emerge out of the annotation, non-linearity, collaboration and innovation, we can uncover just a few of these stories.

The Rock (Arran) (1967), courtesy AGA

The composite landscape Gray builds in Book Four's title page is non-linear in structure. Look to Arran for an example. The island off the west coast of Scotland can be seen towards the bottom right of Gray’s annotated frontispiece. For Gray, it was the site of childhood holidays, an unhappy honeymoon, and excursions with friends including Malcolm Hood - the ‘face of the big bloke’ on the front of Book Four. Gray painted The Firth of Clyde from Arran from Glasgow in 1970. He used sketches he made from The Rock (Arran), which was completed in 1967. It was a commission painted to recall its recipient’s childhood. Which Arran does Book Four depict? Ask me, I’ll say it’s the home-from-home of the Smith-O’Neils and an anchor point for memories we share. Your answer, I imagine, will differ. Gray's composite landscape cuts across time. It is coloured by ink and memory. It's made brighter by new perspectives.

Non-linearity

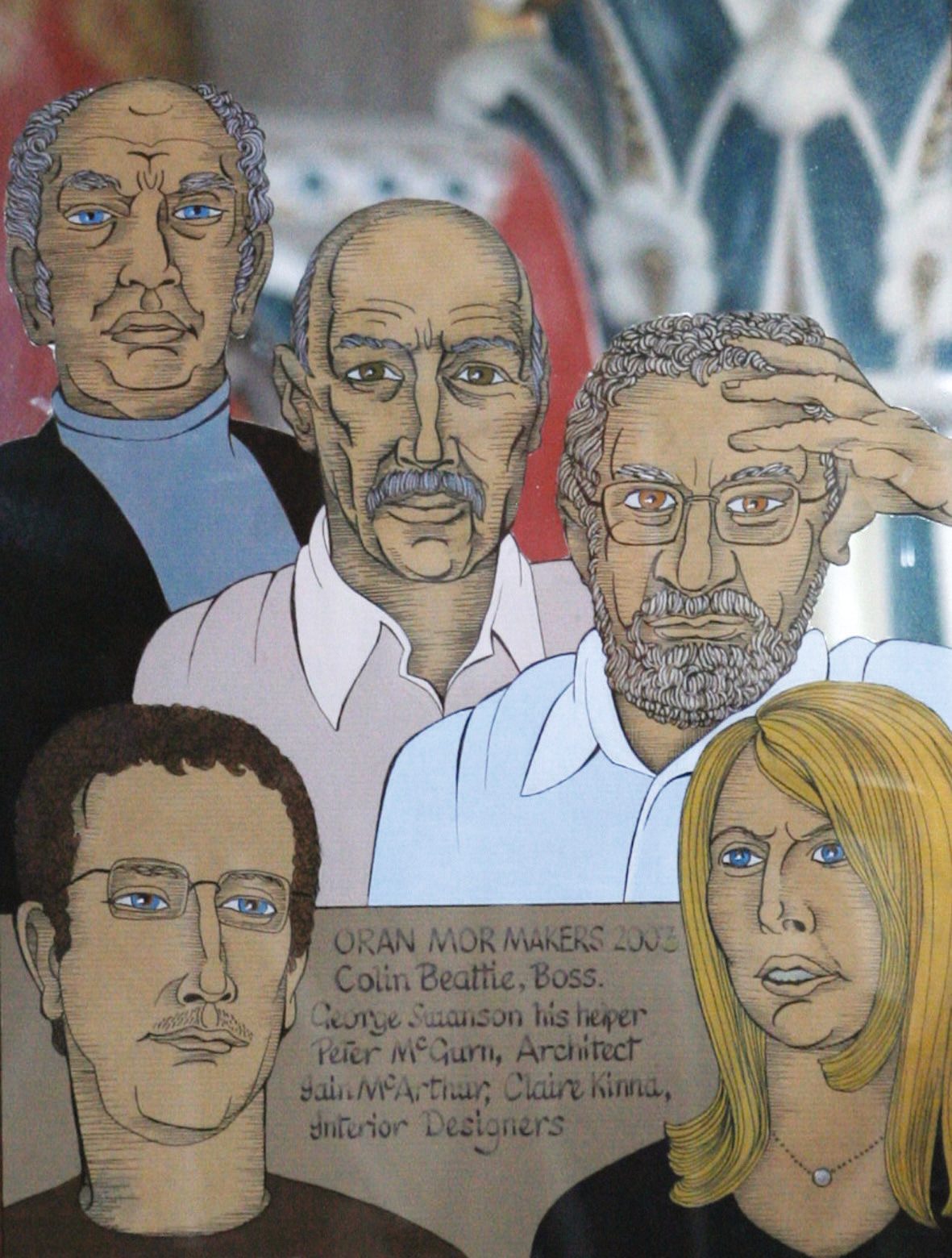

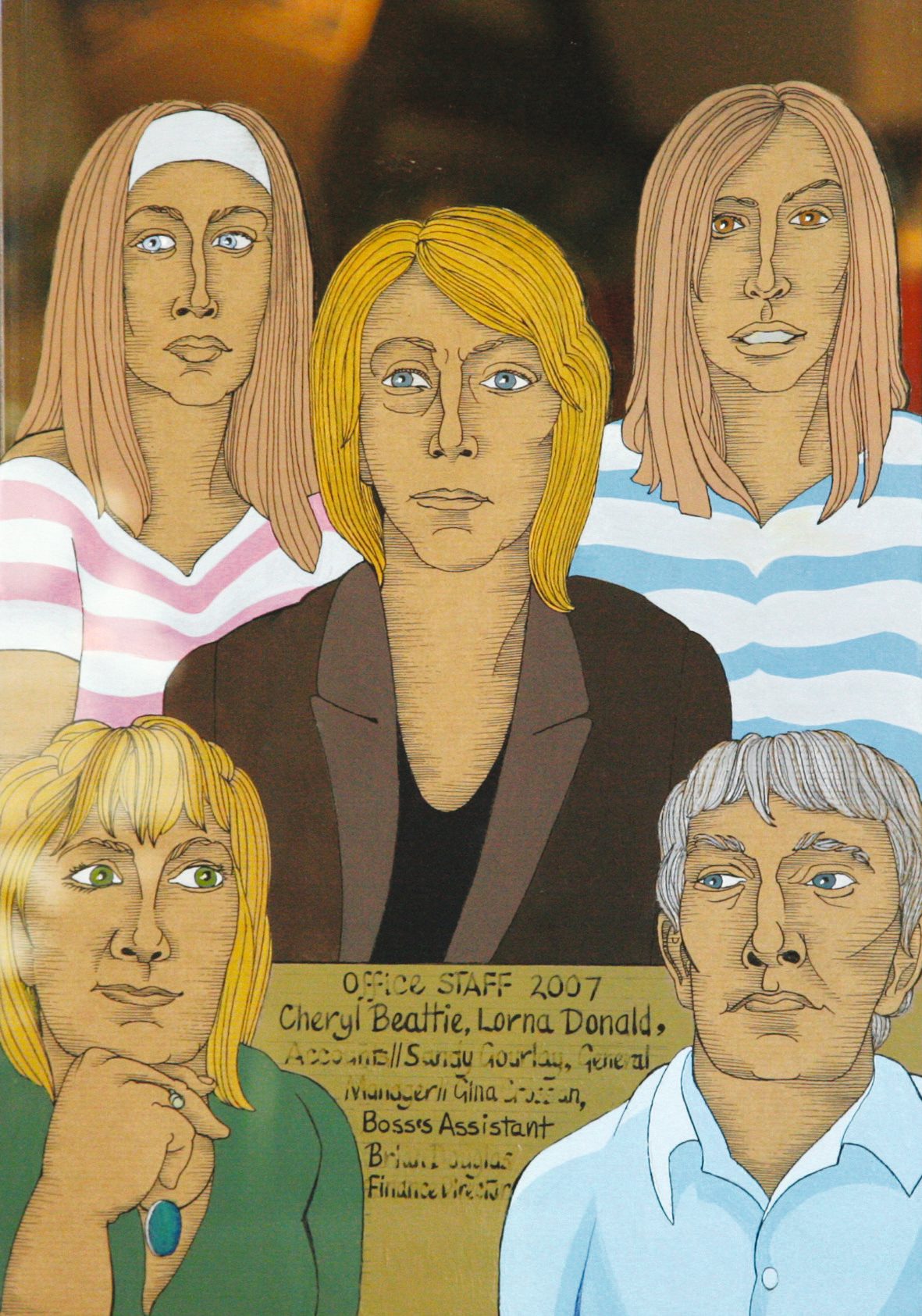

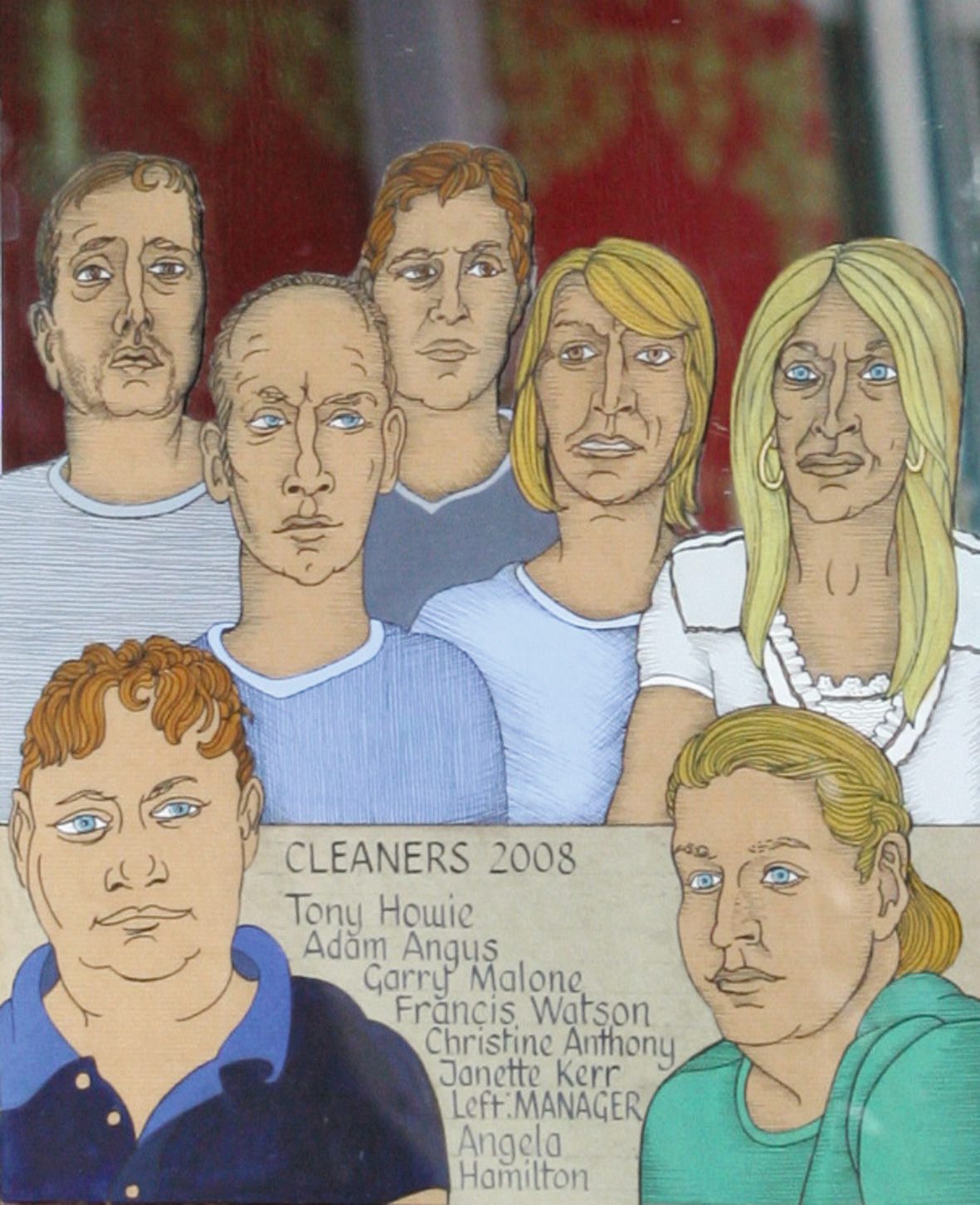

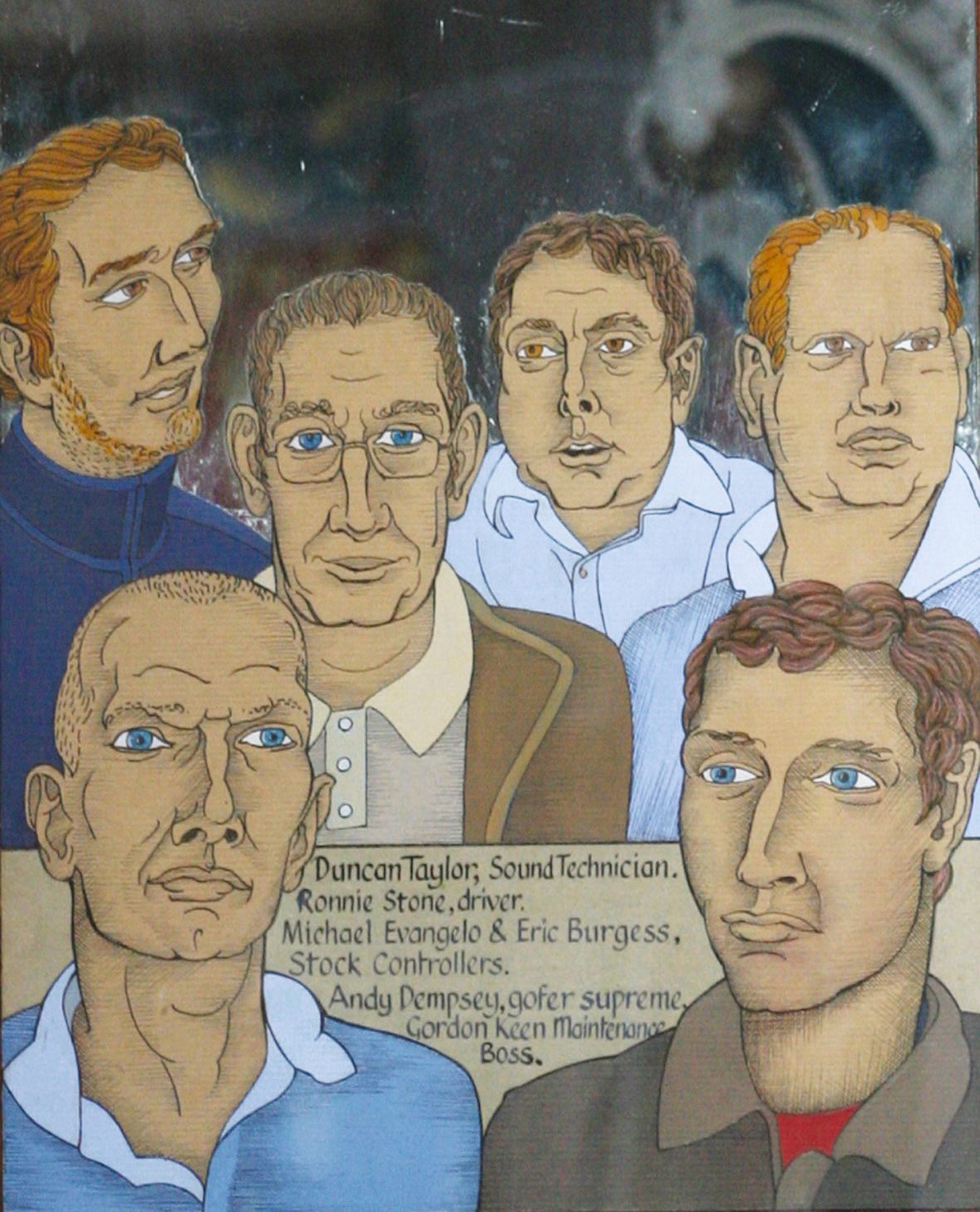

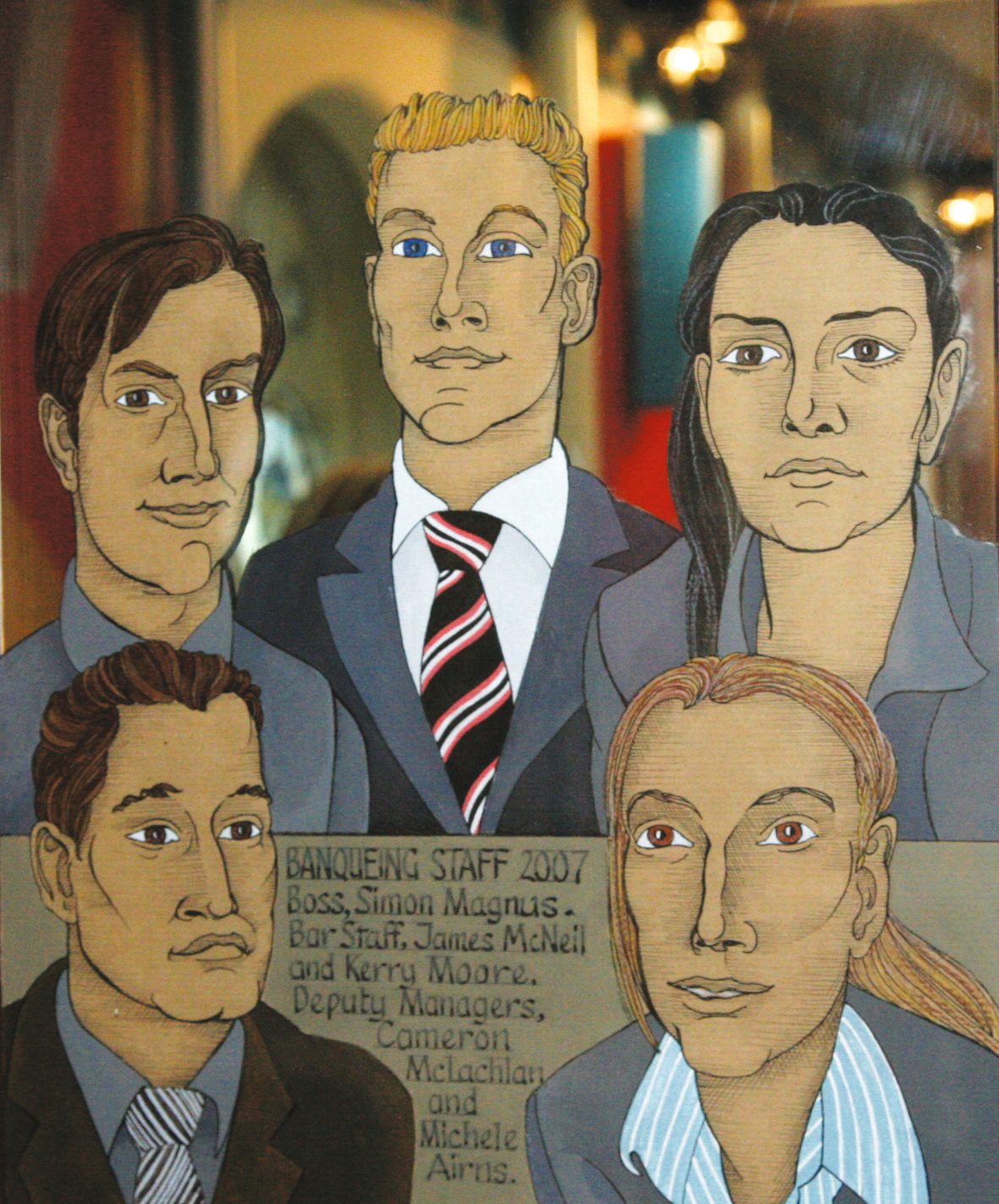

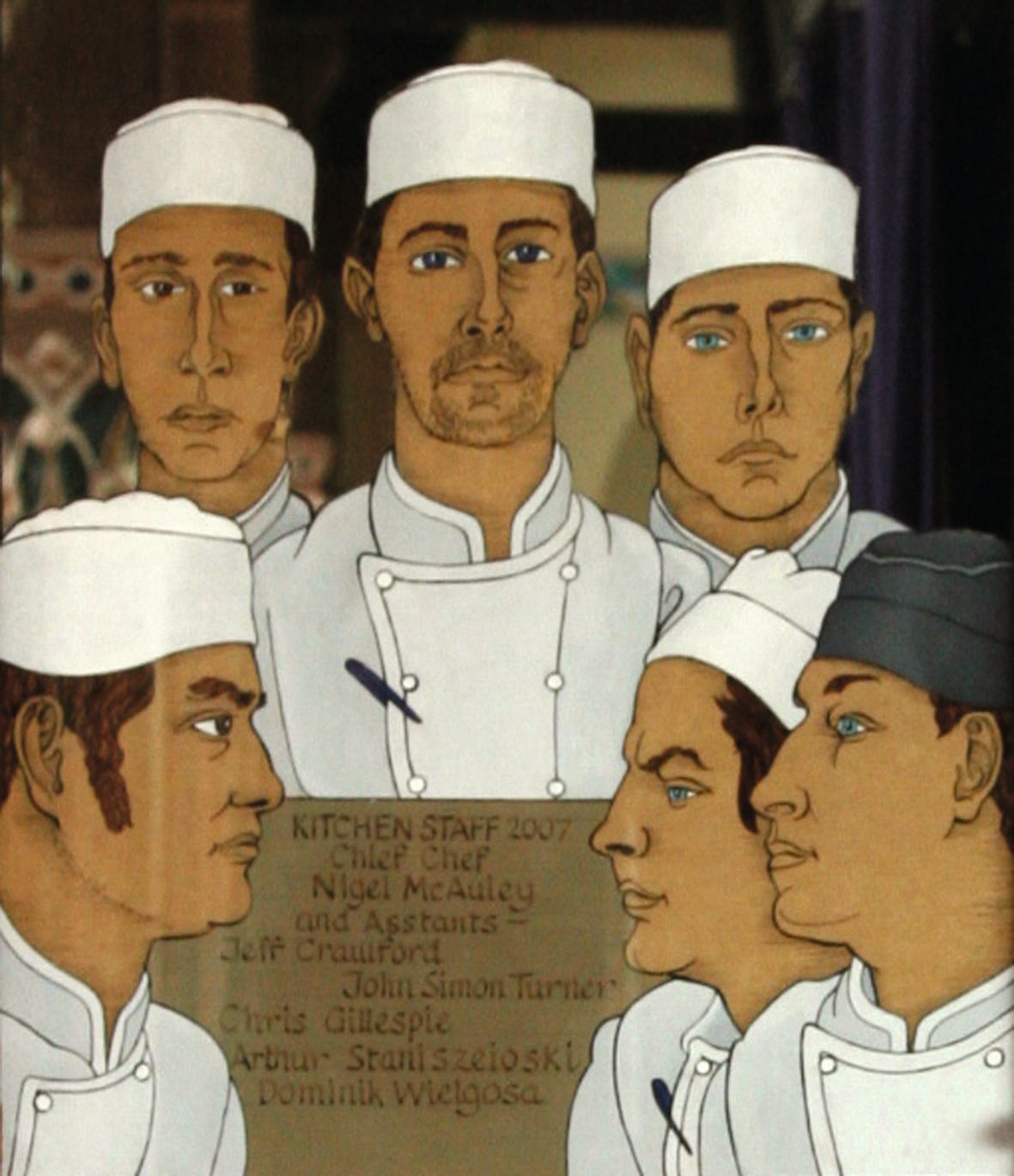

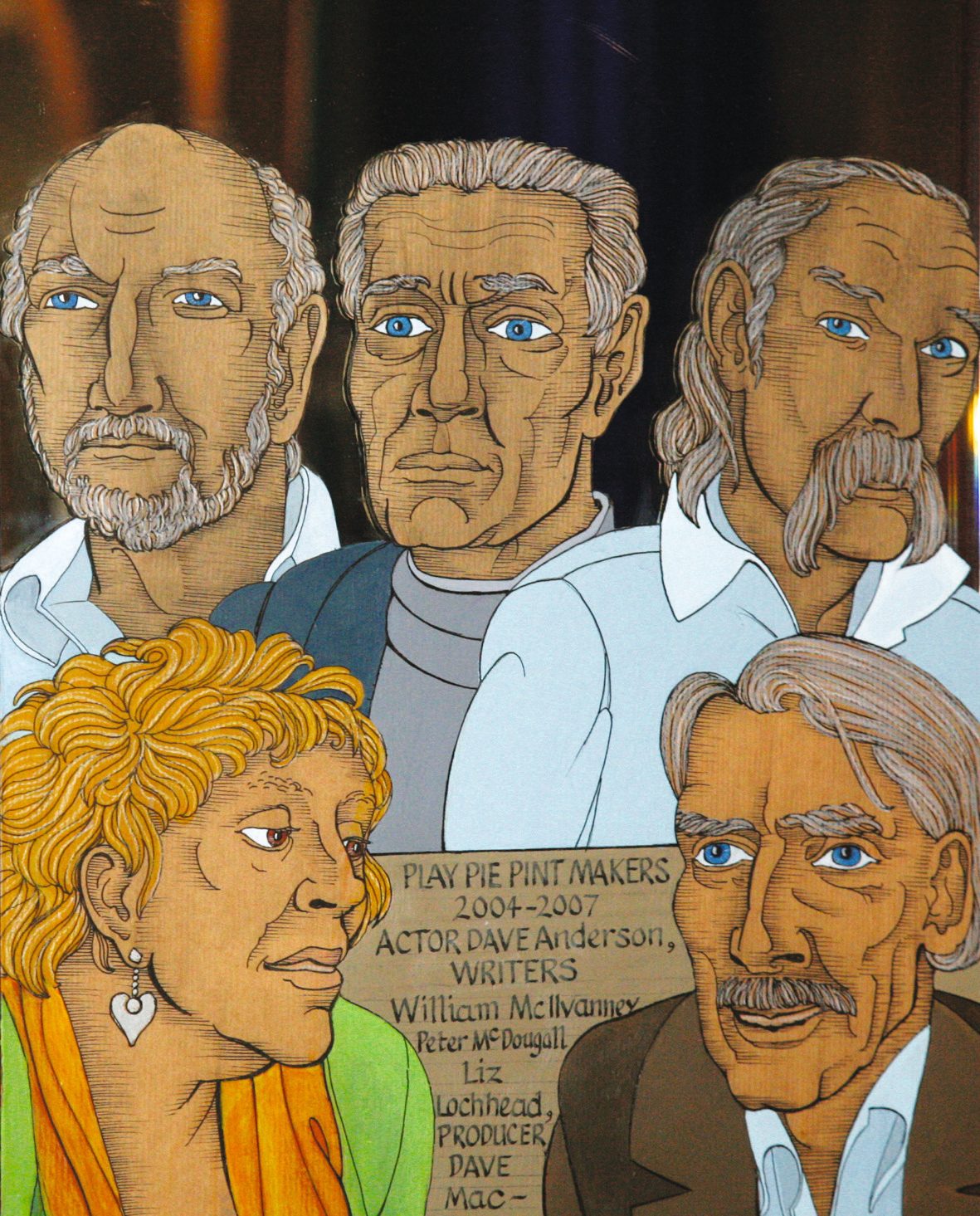

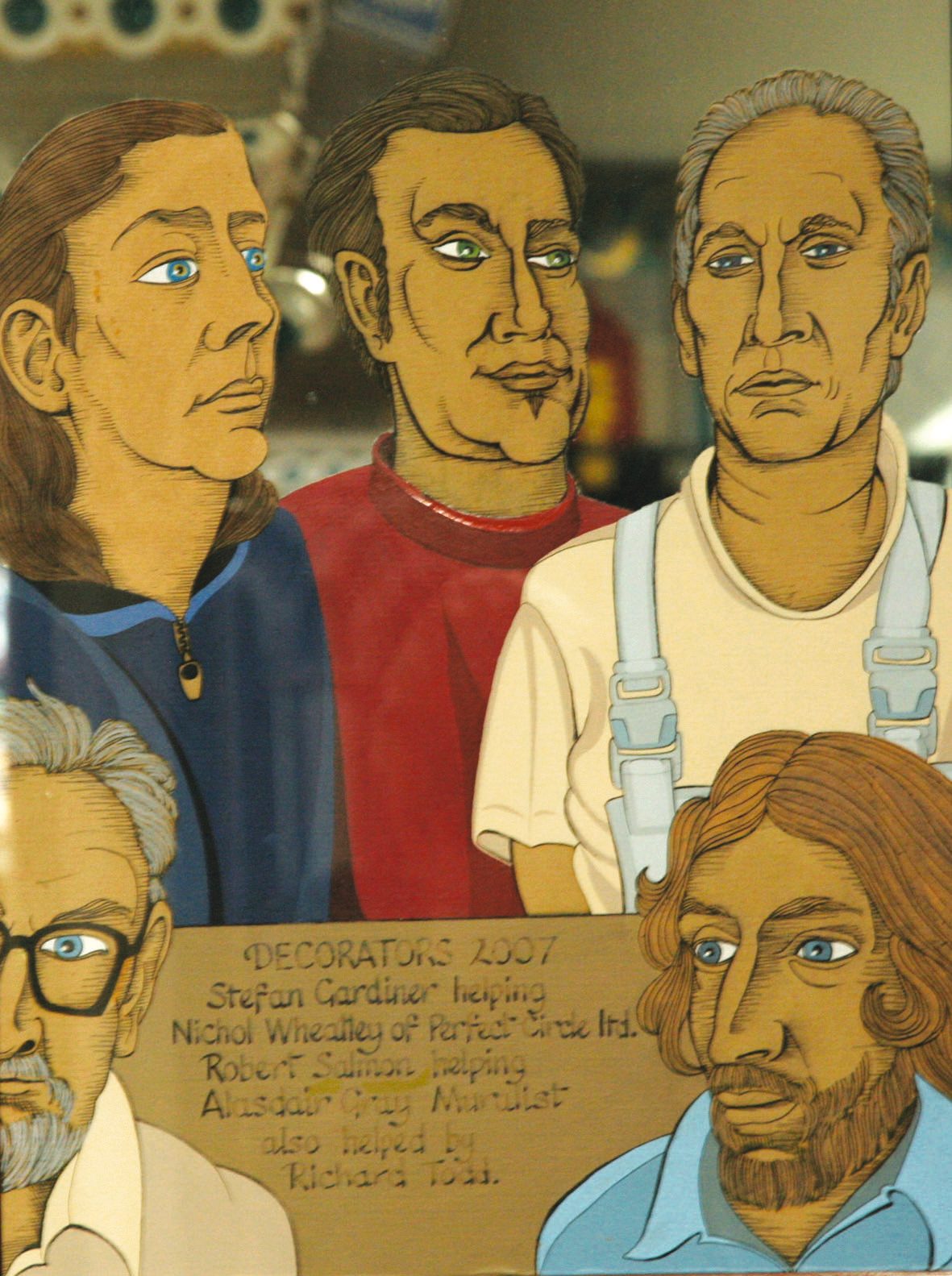

The frontispiece of Leviathan, the inspiration for Book Four's title page, was made with creative input from Thomas Hobbes. It was designed, however, by Abraham Bosse. His name is absent from the cover. The implied hierarchy of authority to subordinate, evident in Bosse's unheeded recognition, is presented within the artwork thematically. The bottom panels show competing authorities, each ruled over by a Sovereign King. The body of the ruler is composed of the blurring-together of citizens' bodies, who turn from the viewer towards their leader. The imagery of Gray's Book Four repeats Hobbes' hierarchical strain, yet its ethos is notably absent from his own practice as an artist and writer. Under the skies of his Òran Mór mural, eight framed panels line the walls. Each depicts staff members who worked as Gray painted his infinite cosmos. Their faces look to the viewer: a reminder they too have stories to tell. The gaze they hold is distinct from the sideways look given to the artist by his then-wife, Inge, in the ledger. It is, perhaps, an indication of a gap in Gray's ability to honour personal relationships in action, as he did working relationships in paint. There is, of course, a crossover between the personal and professional within Gray's work. For Gray, to learn from others is to collaborate. To benefit from the skills of others is to collaborate. To acknowledge whoever was present during the creation process is a form of collaboration. The Òran Mór staff are by Gray's logic, collaborators. Their faces can be read as indices of plagiarism in visual form.

Òran Mór auditorium (2004), Òran Mór owners, architect and designers; office staff; cleaners; maintenance men; Banqueting hall staff; kitchen staff; lunchtime theatre playwrights and producers; decorators Nichol Wheatley, Alasdair Gray, and their main assistants (2004), courtesy AGA

Collaboration

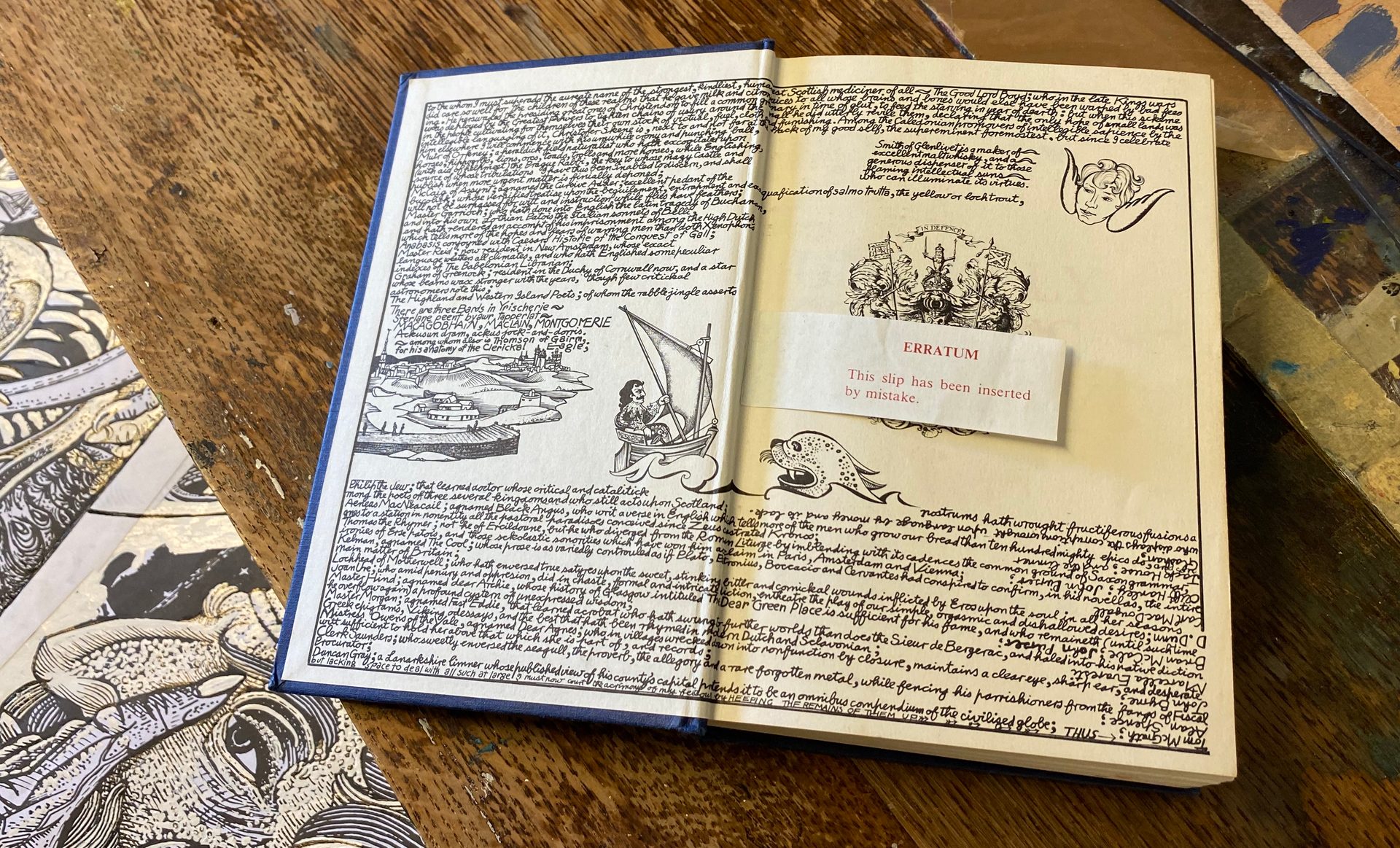

Gray’s visual preservation of his collaborators in his Òran Mór panels, many of whom have since moved on, makes a past moment constantly present. A similar reverence for past influence is recorded in Gray's personal collection of books. Many contain marginal notes marking the impact of certain passages or ideas on his thinking. Gray's habit of revising the annotations made by his younger self often years or decades later, goes some way to demonstrating his innovative methods of embellishing text. Oftentimes, these innovations are playfully self-referential. Gray’s propensity for finding errors and revising content in his apparently 'finished' works is articulated by his long-term typesetter, Joe Murray, in 'A Short Tale of Woe'. The story was written about Gray's The Book of Prefaces (2003) which Murray typeset over more years than he cares to remember. As if pre-empting this situation, in the original edition of Gray's Unlikely Stories Mostly (1983), you'll find an erratum slip. The small slip of paper, typically inserted into a printed book listing mistakes noticed after publication, reads: 'ERRATUM This slip has been has been inserted by mistake.'

Unlikely Stories Mostly (1983), courtesy AGA, photographed by Rachel Loughran in 2022

Innovation

These short narratives, like Joe Murray's short tale, are just a handful of stories that lie within Gray's annotated frontispiece. Each new image has its own story to tell. It's a fact that Glasgow Print Studio’s Claire Forsyth makes clear in a video annotation of Lanark’s Book Jacket. The print she chose to annotate was collaboratively redesigned between the Studio and Gray in 2014. It is one of a limited edition of sixty. Another of the set you've seen before: over the entry point to this exhibition.

Claire Forsyth for ‘Gray Tales, Day Three’, produced by The Alasdair Archive for Gray Day 2022

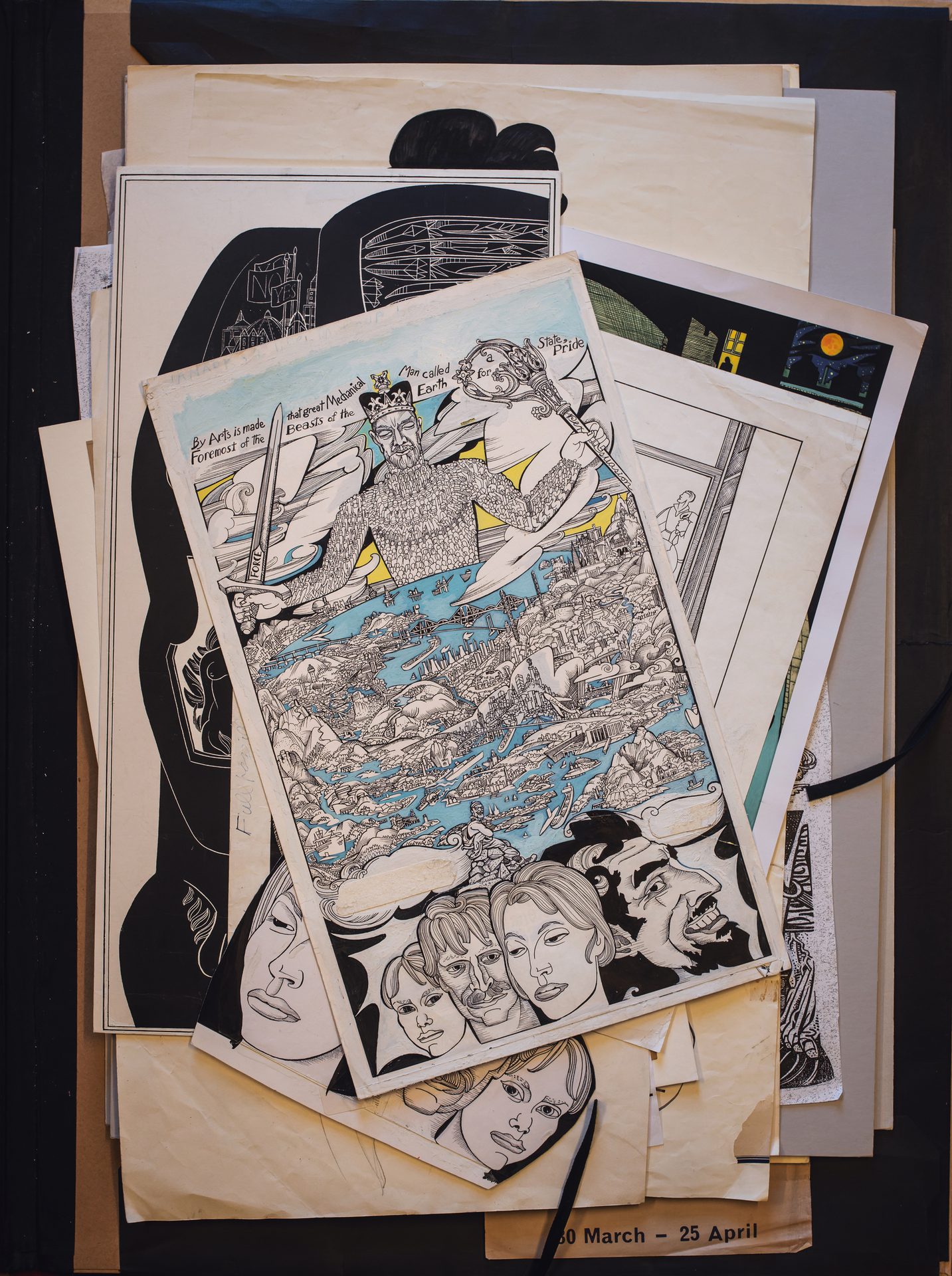

All of the artworks relocated to The Alasdair Gray Archive by Gray’s friend and former gallerist Sorcha Dallas, can be considered as being suspended in a state of incompletion. ‘Finished’ works are revised and made new. Repeated motifs from ‘unfinished’ works are renewed by those that are ‘finished’. The cycle continues, and so it goes. The Alasdair Gray Archive houses many such images within a large plan chest. It was relocated from Gray's domestic studio after his death in 2019. The liminal position of all of Gray’s work - caused by its suspension between states of completion - is reanimated in the way that the chest has been archived. The sketches, source materials, paint and paper that sit within its drawers are preserved in the order in which Gray left them. Yet their redevelopment continues. Visit the archive and you’ll find that each of the drawers can be pulled open, their contents touched and surveyed. No longer waiting for the hand of the artist to revive them, it is the perspective of the viewer that remaps the stories they tell.

Plan Chest, courtesy AGA, photographed by Alan Dimmick in 2021

Look closely at the image and you'll see the drawers of the chest are labeled. From the bottom up it reads: 'PLACES', 'PRINTS', 'ORAN MOR & Hillhead subway for murals', 'Other folk's ORIGINALS & reproduct icons', 'Portraits Figure Drawings'. The top drawer reads: ‘Work in Progress'.

It is in this drawer you’ll find a cardboard portfolio case. Open its ribbon ties. The first image you see is a partially coloured work in progress of Book Four’s frontispiece. The bottom panels are different from the version you looked at earlier. The panels, which usually contain eight symbolic vignettes, are covered over by the face of Andrew as a boy, Gray's own in his thirties, and Inge's as they were drawn in the original book jacket. The trio is joined by artist Alan Fletcher, who Gray met in his first year of Art School. Taylor can also be found on the book jacket of Lanark, in its pages as Aitken Drummond and under his real name in 1982, Janine. He died in 1958, aged 28. Again, past moments become present.

Portfolio in Plan Chest Works in Progress, courtesy AGA, photographed by Alasdair Watson in 2022

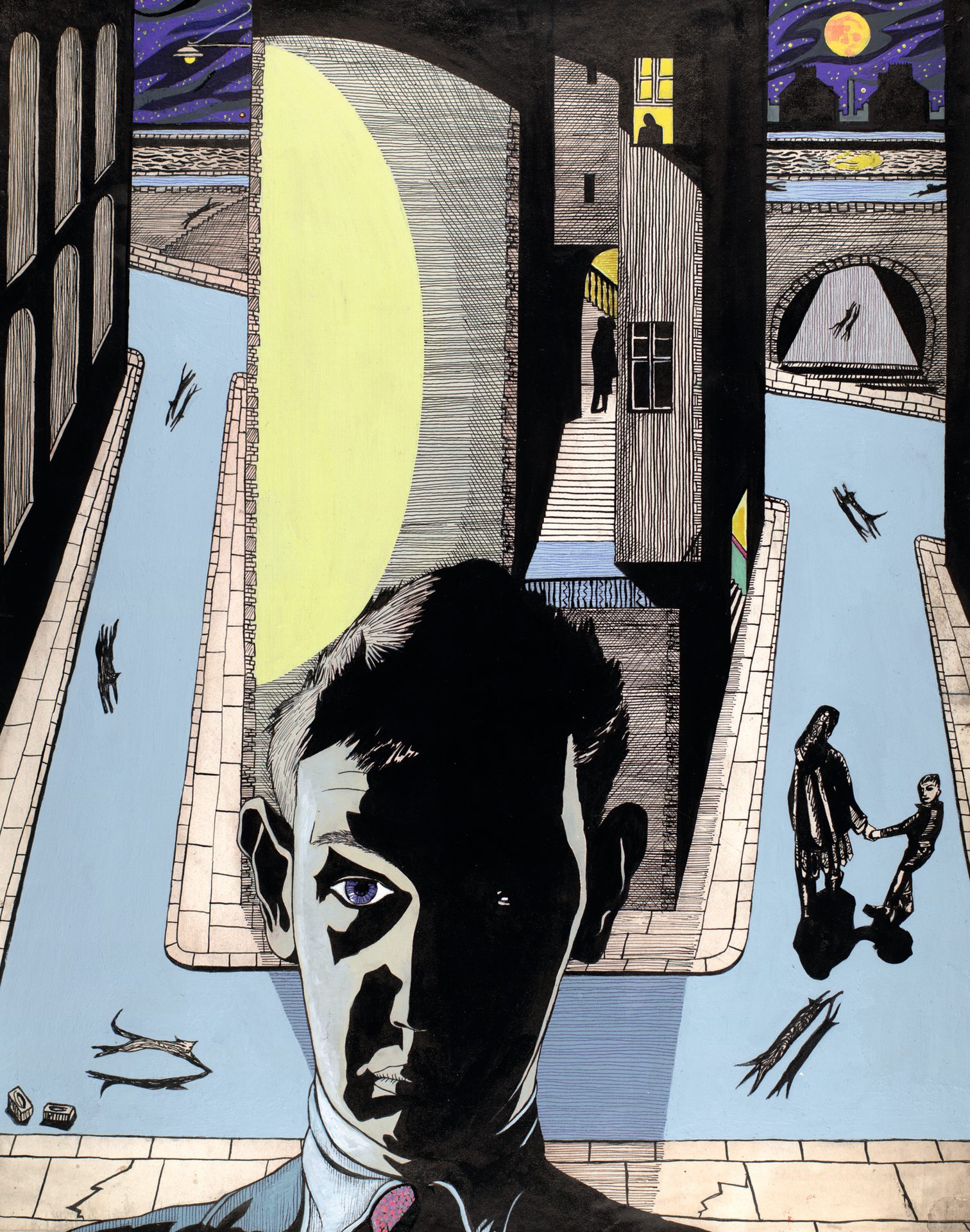

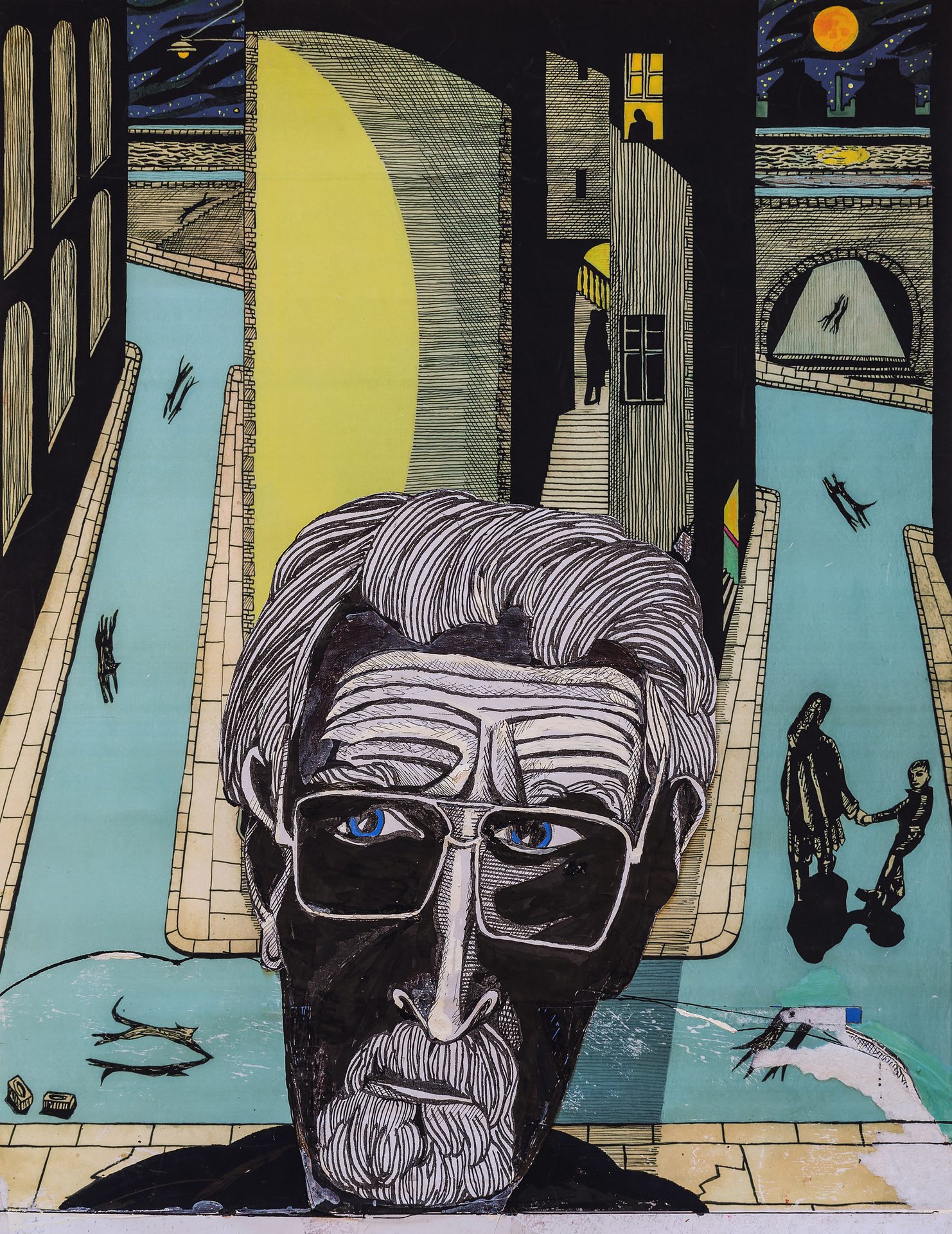

Directly underneath the revised version of Book Four's frontispiece, a face looks up from another image. The drawing is remarkably similar to Gray’s Night Street Self-Portrait, a black and white ink drawing made in 1953. The background to the drawing is composed of two streets partitioned by a tall tenement building. It's a pre-cursor to Cowcadden’s Streetscape. Beside them, a mother and child hold hands. Nine images of the same shadowy cat shift across the surface, seemingly outliving its seven lives. In the foreground, the half-shadowed face of the nineteen-year-old Gray looks outwards. He stares directly at you. Gray added colour to the drawing in 2006 with brushstrokes that made the old image of a young face become new. The face that looks out of the plan chest is different again. It shows the same coloured backdrop, but with the face of Gray as a much older man. ‘We age quickly in this world’, Lanark reflects in Book 4. Here the fantastical becomes real. Lanark’s awareness of the sudden swiftness of ageing, we can assume, is not based solely on the effects of his travels through intercalendrical zones. It is a feeling recognisable to any of us who have looked in the mirror, only to be greeted by a face older than the one we anticipated.

Night Street Self Portrait (2006), courtesy AGA

Night Street Self Portrait, Plan Chest Works in Progress, courtesy AGA, photographed by Alasdair Watson in 2022

Another visible change between the portraits can be observed by scanning the subjects' eyeline. The young man's centered gaze has shifted in the plan chest’s Night Steet Self Portrait. The older man looks sideways. Might we detect in these older eyes a look of wry discernment? Or is it an avoidant deflection? Or even a worried stare?

Each is an open question that has no definite answer. The plan chest's works in progress are, after all, no longer waiting for the hand of the artist to revivify them. They rely on the perspective of the viewer.

Gray said that Lanark was designed ‘to be read in one order but eventually thought of in another'. So too are these images. Pull the elder Night Street Self Portrait out from its position in the portfolio stack. Place it on top of Book 4. Witness the artist give his life’s work a sideways look.

Lanark, Book Four, title page draft, Night Street Self Portrait, Plan Chest Works in Progress, courtesy AGA, photographed by Alasdair Watson in 2022

In the final chapter of Book Four, 'End', Lanark also surveys his life's work. Having travelled through an intercalendrical zone for the final time, after failing to save the city from political and environmental collapse as its Lord Provost, Lanark returns to Unthank an old man at his journey's end. In the novel’s final pages Gray's protagonist looks out from a viewpoint high on the necropolis. This time he stands on its 'glittering spine', viewing Glasgow's magnificence from a different angle as he did as Thaw in Book Two. Surrounding Lanark is carnage on an apocalyptic scale. Floods, burning buildings, skies blackened with smoke – images taken straight from a Gray mural. Undaunted, Lanark gives the vista a sideways look: 'a long silver line marked the horizon...he looked sideways and saw the sun coming up golden behind a laurel bush, light blinking, light dancing among shifting leaves'. It is then that Lanark, 'drunk with spaciousness, turned every way, gazing with wide open mouth and eyes as light created colours, distances and solid, graspable things close at hand.' Unlike Lanark of Book Three who stared horrified at a world in flux, or young Thaw for whom spaciousness and conflict collide, the old man revels in the multiple perspectives carouselling before his eyes.

As the flood recedes back down the slope, Lanark learns of his own imminent departure from the landscape. The news that he will die the following day at a precise seven minutes after noon, Lanark accepts with only a little hesitation:

– 'I ought to have had more love before I die.'

‘That is everyone’s complaint’, the death messenger replies. As we observe Lanark for the final time, he looks skywards. 'He was slightly worried, ordinary old man but glad to see the light in the sky’. There his narrative halts.

Self Portrait with Yellow Ceiling (1964), courtesy AGA

[THIS PAGE HAS BEEN LEFT BLANK FOR REASONS]

The narrative halts, but does not end. After what appears to be the final lines of Book Four, the reader is met with a blank space on the page.

Below the empty space is a verse, adapted from another by poet and musician John Purser.

It reads:

I STARTED MAKING MAPS WHEN I WAS SMALL

SHOWING PLACE, RESOURCES, WHERE THE ENEMY

AND WHERE LOVE LAY. I DID NOT KNOW

TIME ADDS TO LAND. EVENTS DRIFT CONTINUALLY DOWN,

EFFACING LANDMARKS, RAISING THE LEVEL, LIKE SNOW.

I HAVE GROWN UP. MY MAPS ARE OUT OF DATE.

THE LAND LIES OVER ME NOW.

IT IS TIME TO GO.

It is time to go for us too. We travelled across an expansive vista. We looked beyond multiple horizons. Our journey has reached Gray's 'End'. This ending, like that of Lanark's four books, however, is equally a beginning. Just like the 'clear outlines' of Gray's horizon story, which dually invite us to look beyond what is firmly stated, the final note of Lanark is not really an ending at all. 'My maps are out of date' Gray states. ‘The land lies over me now / it is time to go'. Though the lines depict departure, they equally invite us to update an old map with new perspectives.

A similar ending can be traced back to Gray's earliest short story. In the final lines of 'The Star', a young boy from Glasgow swallows the star he saw fall beyond the horizon. His perspective is suddenly transformed: '[the] world receded like a rocket into a warm, easy blackness leaving behind a trail of glorious stars, and he was one of them'.

Where one narrative 'ends', another begins.

It is here that I really hand over to you. Gray's horizons are vast: they demand to be read and re-read, reimagined and re-mapped with new perspectives. So, whether you started out in an exhibition space, in front of a screen, or as a wee boy from Riddrie staring across a starlit horizon, think of this journey through Lanark as a mere prologue to the one on which you are about to embark.

End note: If you would like just a little more guidance on the next leg of your journey head to the Index of Plagiarisms. You'll find an index of sources and further reading in addition to more information about the exhibition's contributors, including its main collaborator The Alasdair Gray Archive.

The Star (2005), courtesy AGA

GOODBYE